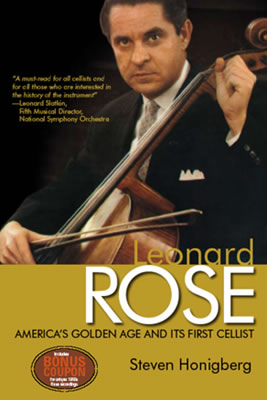

LEONARD ROSE:

AMERICA’S GOLDEN AGE and ITS FIRST CELLIST

Leonard Rose Videos by Steven Honigberg

As author and professional cellist, Steven Honigberg (b. 1962), complements his biography’s subject with a musician’s ear for language and the highest technical expertise. He currently plays on a 1732 Stradivarius (the “Stuart”), holds degrees from The Juilliard School, and combined with experience writing about legendary cellists, has produced a comprehensive first biography of America’s “first cellist.”

The cello has dominated the author’s personal life since kindergarten and two of its history’s most respected performers, native-born Leonard Rose and Soviet-American Mstislav Rostropovich, have entwined as recurring themes throughout his professional life.

As a protégé in Rose’s final years, Honigberg retains the wealth of knowledge his subject imparted to students, as well as an abiding sympathy for the man. That intimate relationship of the past provided unparalleled access to Rose’s living colleagues and classes, from his best known pupil, Yo-Yo Ma, to internationally acclaimed stars with whom the pedagogue collaborated, such as Van Cliburn, Lorin Maazel, Emanuel Ax, Pinchas Zukerman, Itzhak Perlman and more. Likewise, the biographer’s exceptional music credentials served as entrée to befriend Rose’s heirs.

Steven Honigberg grew up in a Chicago-area musical household where he began cello lessons at age 5 and encountered Leonard Rose via the family’s LP collection.

Recordings of favorite Romantic-era literature and Rose’s sonorous cello captivating the boy. He recalls a vivid childhood memory of one cover photo of his future teacher; the intense stare into the camera inexplicably attracted him, long before hecould envision a move to Manhattan to learn from the intense man in the picture.

In his teens, Honigberg won a number of regional competitions that awarded him solo appearances with the Youth and Civic orchestras of Chicago; at Interlochen, he performed Bloch’s Schelomo as concerto soloist with the World Youth Symphony. And at age 16, the Chicago Symphony’s distinguished youth auditions granted him eight solo appearances with one of the nation’s top-five orchestras. In the early 1980s in New York, while he completed his Masters degree at Juilliard, the author won additional awards.

One competition sponsored his formal debut at Carnegie Recital Hall. Through one at the school, he won the opportunity to perform as soloist in Strauss’s Don Quixote with the Juilliard Orchestra.

In 1984, the author was handpicked by cellist-conductor Msistlav Rostropovich to join the National Symphony Orchestra, a position he holds to this day. Eerily similar to the Rose biography’s chapter devoted to personal events of 1964, “Darkness and Light,” the year 1984 marked the author’s period of triumphant and tragic transitions. Within months, he graduated from college, presented his New York recital debut, appeared as soloist in Alice Tully Hall, accepted the Washington job. And – Leonard Rose died.

The entire cohort of Rose alumni concurred that his loss was immeasurable and, in retrospect, would agree his influence continued. For the author, a baton was handed off from Rose to Rostropovich, from the end of school and launch of his profession. He played in the National Symphony’s cello section under Rostropovich for a decade, during which time in 1987 was the only American winner of the Scheveningen International Music Competition in Holland (1987) and cited by the influential magazine Musical America one of a select group of 1988 Young Artist(s) “to watch.”

In the footsteps of his biography’s subject, he constructed a career as member of symphonic and chamber ensembles, as recitalist and concerto soloist, performing in an Eastern metropolitan area during the regular season and at various U.S. summer festivals.

The affiliation with Rostropovich produced one of Honigberg’s crowning literary and musical achievements, to date. In contrast to Rose’s fame for perfecting the cello’s standard repertoire, Slava championed contemporary works, adding some 150 new pieces from around the world to the cello canon. When Rostropovich died, Honigberg dedicated himself to a verbal and sonic memorial project, “Homage to Slava.”

The author-cellist performed and recorded modern pieces for solo cello composed for Slava by such disparate creators as Penderecki, Walton, Vainberg, Ginastera, Stutschewsky, and Lutoslawski. Additionally, Honigberg recorded two cello études composed by Rostropovich. A pair of works written specifically for Steven Honigberg by American composers, David Diamond and Robert Starer, round out the memorial recording.

The author’s lengthy biographical essay, “Homage to Slava,” accompanied the eponymous CD, appears in print and on the web.

The author’s writing career began shortly after he settled in Washington, D.C. A majority of his published work has focused on short biographies on renowned cellists. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, for a professional music trade publication, he wrote a series of columns under the heading “Remembering the Legends,” – a few subjects were Leonard Rose, Pierre Fournier, and Frank Miller (who was Rose’s cousin and during Rose’s teenage years, a mentor). In addition, Honigberg published a feature about Gregor Piatigorsky’s influence on the National Symphony’s then-principal cellist, John Martin. And from an autobiographical perspective, Honigberg published “A Cellist’s Life at 40,” in the Potomac Review (Spring 2003).

From 1994-2002, Honigberg served as chamber music series director at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, where a primary duty required writing of some 40 overviews on the gamut of topics at the intersection of music and the Holocaust. These brief articles ran on the museum website and the author delivered them as speeches in Washington, D.C. and venues across the country.

As pedagogue, Leonard Rose believed all collaborative experiences – conductors witnessed, soloists accompanied, chamber partners, which amounted to the spectrum of the 20th-century’s stars from America and abroad – each imbued him in musical knowledge or inspiration, and the sum of these experiences was what he imbued in his protégés. The author was one of the privileged handful to whom Rose passed that torch – a crucial aspect to Rose’s life that requires a Rose pupil’s elucidation in any life-story.

Honigberg regards himself as logical and pragmatic, nevertheless fails to adequately comprehend how Leonard Rose’s LP photo lured a child who could not fathom the picture’s emotional expression and, in spite of his mentor’s death and time passed, how Rose’s presence and active influence in his own musicianship were ongoing.

Ultimately, the mysterious feeling drove the author to seek out fellow alumni, compelled him to inquire if others shared the bizarre experience of Rose’s continual effect on their artistry. In response to the curiosity, he swiftly received a hundred pages of concurring thoughts and anecdotal remembrances in praise of “America’s first cellist.”

The tributes to their teacher and collective disappointment that Rose deserved a full-length biography sparked Steven Honigberg to undertake the present volume. As author-cellist, he started with soliciting his own group of colleagues, recollecting a host of first-hand observations, and noting information best conveyed by a professional cellist.

The paucity of extant material about the brilliant, prolific musician was, at first, stunning. From the foundation of initial queries to his cohort, the author-cellist began several years of research and the writing of LEONARD ROSE: AMERICA’S GOLDEN AGE and ITS FIRST CELLIST.

Steven Honigberg writes in the book’s Introduction, “The lives of thousands of musicians and music-lovers have been touched by Leonard Rose’s exquisite artistry as a soloist, chamber musician, and orchestral member, yet none so profoundly touched as the 200-250 individuals privileged to call the great cellist, ‘my teacher’.”

Notes received from those who have read Steven Honigberg’s biography of Leonard Rose:

“I give you fondest Congratulations for the fascinating book you have produced. It will amuse you to know that the very first time he sat on stage – at the Curtis – I played with him."

-Ralph Berkowitz (age 101)

“Thank you for publishing the marvelous book on Leonard Rose. Mr. Honigberg’s work is a treasure: an immense gift to all cellists and to the music world.”

-Michael Fitzpatrick

“I write in response to the wonderful new biography of Leonard Rose which I’ve just devoured in a single, day-long sitting.”

-Jason Calloway

“This book is great. One of the best bios of a musician I know. I am a violinist with the Philadelphia Orchestra.”

-Davyd Booth

“This book is a great glimpse into his life, and I congratulate you on your accomplishment.”

-Gerald Kagan

“Congratulations. I was extremely impressed with the detail and finesse with which you told the whole story. The layers of life worked out to fit together and added up to a monumental tale. It was fascinating how you put his life and artistry into the context of the musical culture of the time period”

-Ron Shawger

“Thank you for the tremendous amount of research you did on your fascinating and well-written book.”

-Catherine Lehr

“The book is WONDERFUL and I have recommended it to many.”

-Karen Beck

LEONARD ROSE: AMERICA’S GOLDEN AGE and ITS FIRST CELLIST

is available for purchase from Amazon.com